Key factors global transition should focus on

A new report listed several realities that must be addressed for the energy shift to succeed.

Amidst efforts to fuel the energy transition, a new analysis by McKinsey Global Institute listed several physical realities that the shift must tackle to keep the momentum going.

In a report published April, McKinsey Global Institute said one of the factors that needs to be addressed is the flawed but high-performing energy system.

For instance, a gas turbine power plant can move from full shutdown to generating power at full capacity in less than ten minutes. And fossil fuels are a capable source of high-temperature heat in the production of industrial materials, whilst their chemical flexibility enables them to be used not only as sources of energy, but also as feedstocks—for example, they provide molecules on which plastics are based.

However, the system still faces inefficiencies, with around two-thirds of all energy being wasted today, mostly due to low energy efficiency in the conversion and use of fossil fuels.

“The energy transition would therefore require replicating the benefits and performance of the current system whilst addressing its downsides,” the report read. “Overall, the energy transition will require both continuing to improve the performance of low-emission technologies and bringing them together in new ways to deliver high performance.”

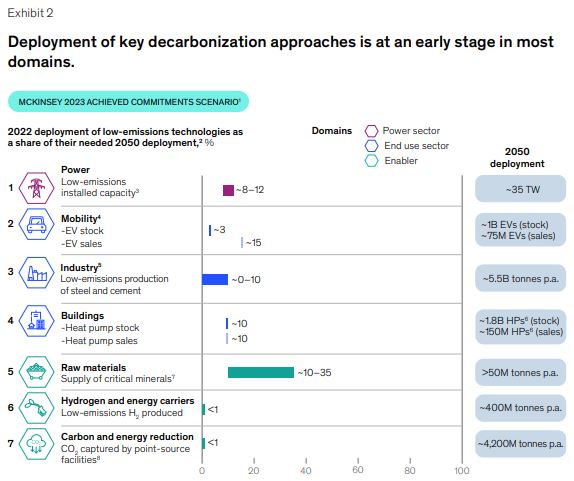

Another reality is that only about 10% of low-emission technologies needed by 2050 to meet global commitments have been deployed. To transform the energy system would require the substitution of billions of physical assets.

In a 2023 report, McKinsey said that about one billion electric vehicles (EV), more than 1.5 billion heat pumps, and about 35 terawatts of low-emission power generation capacity would need to be deployed by 2050 to reach national climate targets.

Whilst there has been momentum toward this, “deployment of low-emissions technologies is only at about 10% of the levels required by 2050 to meet global commitments in most areas—and far less than that in others.”

“For instance, less than 1% of the 90 million tonnes of hydrogen produced today comes from low-emission production. Overall, therefore, the energy transition is in its early stages,” it added.

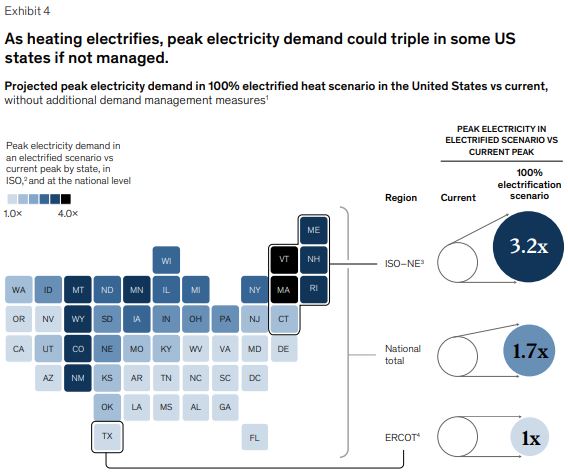

Another reality McKinsey cited is that electrifying heat will require managing higher demand peaks.

The heating and cooling needs of buildings account for almost 85% of total carbon dioxide emitted from buildings, with space heating and water heating responsible for more than 75%.

The need for heat is currently largely met by burning fossil fuels—for example, in gas boilers. Fossil fuels could be replaced by using electric options. Heat pumps are highly efficient heating technologies and the main option being explored in most markets.

But sweeping electrification of heating in buildings will only add another layer of demand to the power system.

“Action to minimise peaks—and therefore how much power capacity is required in the system—could be implemented, through a combination of more efficient models of heat pumps, more use of heating technologies that combine electrification with other options… to limit use of electricity on the very coldest days, or even smoothing the demand for power by shifting demand for heating to different times of the day,” the report read.